The International Keyboard Institute and Festival, in New York City,

Lessons and Masterclasses Open to the Public, July 17‑31, 2011.

|

|

Boyk Joins Renowned Piano Fest in NYC!

the only southern california pianist on the faculty of

"the world's foremost piano gathering"!

The International Keyboard Institute and Festival, in New York City, Lessons and Masterclasses Open to the Public, July 17‑31, 2011. |

Piano Lessons with James Boyk

Studio in West Los Angeles

Acclaimed Recording Artist & Teacher

Pianist in Residence 30 years, California Institute of Technology.

Author of To Hear Ourselves As Others Hear Us.Lessons in Technique, Interpretation, and Performance Preparation

for serious amateurs, pre-professionals, professionals, and teachers.

Inquire about lessons.Video & Audio -- James Boyk and students.

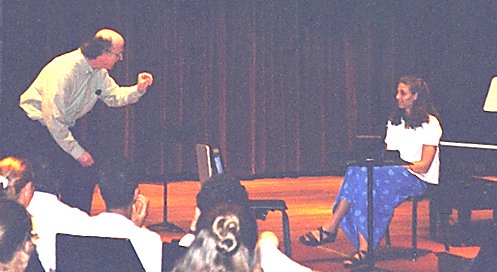

With student Saiko Okawa, heard in recital at

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

on radio in Los Angeles & San Francisco,

and in concert at California Institute of Technology.

Contents

Video & audio of James Boyk and students

Comments from students

The right teacher?

James Boyk's concert recordings

Email notes with students

JB notes to self after two unusual lessons

For more insight into James Boyk's teaching . . .

Comments from students

"An unforgettable experience. Exceptional richness both as an artist and as a teacher, as well as an original approach to music and a powerful capacity to get the best out of those who work with him."

"Wonderfully enthusiastic and effective teacher. While ever eager to convey new and fascinating insights into a topic of discussion, he would always listen to what I had to say."

"His attention to the physicality of playing piano is far beyond anything I've experienced with other music teachers. Knows how to think outside the box and tailor lessons to get the most out of his students. Studying with him has been a tremendous inspiration to me."

"His acute sensitivity to the details of a performance, their relationships to what is written down in the music, and their connection to the overall effect make him a superb coach, able to temper his comments to the performer's level of receptiveness and technical ability to put them to use...."

"Transformed my entire approach to the keyboard."

"Jim's lessons are special and memorable. He would say, 'Of course! What's the point of a lesson if you don't remember it?' If you've used his book, 'To Hear Ourselves As Others Hear Us,' you'll realize that the technique it describes, though laughably simple in its premise, is astonishingly effective at improving your musical ability. If you really and truly believe in the obvious things he says, you will literally astonish yourself.... Jim's peculiar gift is that he understands that every person learns differently... an unparalleled teacher in my experience."

"Lessons were a revelation. I never worked like this before. All the images, the ways of learning.... A very systematic, broad view of a piece, musically and technically; you know of tools, new tools. You help in laying out the problem and finding the appropriate solution. Not in playing a hundred times the same passage, but in thinking about it...."

"You really need to stick a brief notice on your website to the effect that lessons with you are addicting. I can't imagine going back to the 'old style' lessons now. WARNING: Lessons with James are guaranteed to have certain serious and long-lasting side effects. Do not undertake lessons unless you are prepared for the following reactions: 1. A change in your perception of what you need to know in order to play well, 2. A strong anticipatory addiction to your next lesson, and 3. A likely inability to benefit from lessons from the majority of piano teachers in your area."

The Right Teacher?

Am I the teacher for you? The question is hard to answer because every student is utterly individual. One student, highly intuitive, responds to visual imagery. The next one, highly verbal and analytical, responds to logical instructions almost in the style of a computer program. Each is left cold by what works for the other. Both are musical, both are intelligent; what differs is the style of their intelligences. Thus, while principles of piano technique are constant, the way to teach them will vary enormously; and the same goes for every aspect of the work.

So, I simply try to provide useful information here to help you decide whether to audition with me. There are comments from students, email exchanges with students, notes I wrote to myself about lessons, and so on. Read and decide for yourself.

It may be useful to know that I've performed professionally since my teens, and my concert recordings have been warmly reviewed. I've taught piano technique to other piano teachers; for instance, in Yamaha International's clinics for its 100 top teachers in North America. As Pianist in Residence for 30 years at California Institute of Technology (Caltech), I gave solo and ensemble concerts and more than 800 informal weekly sessions of music and talk, and also gave lessons to undergrads, graduate students and faculty members. (I still teach Caltech students and others in my Pasadena studio as well as my home studio in West Los Angeles.) My little book for students and teachers of all instruments, To Hear Ourselves As Others Hear Us, has been received warmly by reviewers and famous performers, and adopted by private-studio teachers and university music departments.

I might be a good teacher for you if . . .

. . you're looking for piano technique that makes sense in terms of how the piano and the body work.. . you expect music interpretation to make sense to both heart and mind.

. . you want to convey emotion to an audience more intensely.

. . you'd like to be able to start from a score you've never seen or heard, and with a reasonable amount of time and effort, end up with a performance that's expressive, physically comfortable–and memorized.

. . you want your questions welcomed–and answered.

. . music and the piano are important to you.

On the other hand, I'm not the teacher you want if . . .

. . you are sure that thought and analysis are opposed to feeling.

. . you want to be passively turned into a pianist and musician instead of actively turning yourself into one.

If you call or write about lessons, then after some preliminary discussion, I may suggest you come for a combined audition and first lesson. If we both feel positive after this, we'll have five or six weekly lessons, and then decide whether to go on. As a performer-teacher, I'm expensive, so studying with me means a substantial financial commitment.

–James Boyk

From Reviews of James Boyk's Concert Recordings

(Over the period 1978 - 2007)

"Boyk is no doubt an outstanding pianist endowed with remarkable feeling for the music's innermost emotions." –Musik och Ljudteknik (Sweden) | "Bach's Chromatic Fantasy & Fugue so perfectly interpreted and played that it brought tears to my eyes and sent a chill down my spine." –Hi-Fi and Home Theatre Technology (Australia) | "Boyk plays the very devil out of this [Prokofiev Sixth] sonata...." –Stereo Review | "Unbelievably precise, his musical concept extraordinarily definite. We rank his 'Pictures at an Exhibition' among our reference recordings." –HiFi Magazin (Hungary) | "Perhaps the most distinguished interpretation [of 'Pictures at an Exhibition'] I've heard.... The feeling of 'coming close to the vision of the composer' is strongly present. In this live recording in front of a devoted audience, the playing is powerful and full of life, yet with no loss of concentration." –Musik och Ljudteknik (Sweden)

Vivian Fan,

and violist Luke Maurer.

...in JB's Alive! with Music at Caltech,

with 'cellist Kay Jhun, violinist Nick Knouf, and pianist Dan Rogstad.

Students email me after each lesson, saying what we covered, what was said, what they're working on for next time (and how), and anything else they think important; and raising any questions that have occurred to them. I respond before the end of the day. Benefits: 1. Writing the notes focuses the student's attention. 2. The exchange becomes a study guide for the week. 3. Errors don't get built in by a week's practice. 4. Because I summarize the notes for myself just before the next lesson, no time is wasted in that lesson on "Where were we?" The process takes me an additional 15-60 minutes per student per week, but is worth it. I invented this technique in 2005, if one can "invent" such an obvious idea; which, however, no one else seems to be doing.

STU 1: Scales: B major in then out [i.e., contrary motion inward, then outward, two hands] is new reference [for 'most comfortable scale']. I suggested that this was even better than E major because the thumbs going in did not coincide with one another, hence less reaction force was generated.

JB: Good thinking. It was gratifying that [another student], listening from the other room, noticed how well you played the B scale, and spontaneously complimented it.

STU 1: Bach fugue: We discussed how to make the downward fifth jump in the countersubject [cs] noticeable when the second note coincided with one of the other voices. When the cs is in the alto, can play the note with both hands - this presents a small difficulty in the stretch of the right hand, but if the subject is detach�, this is no problem. This approach won't work when the cs is in the soprano however on the bass entry, as the left hand is busy with its own two voices. I suspect another solution is thus necessary....

JB: Interesting. You think clearly about music and piano!

STU 1: Chopin [Polonaise E-flat minor]: will record in the next day or two. Things to watch - last note before fermata in A section was a bit gross (think instead of the 2 or 4 note group); B section was slower first time but in tempo second time; run was a bit messy.

JB: Right.

...at the University of Toledo,

With pianist Jennifer Markwood.

Email notes, example 2:

A gifted elementary student, a C.P.A. in her 50s. She has written a book about our first year of lessons. These notes were from early in the year.

STU 2: That was exactly the lesson I wanted. I've been worried all week that I didn't know how to learn at the new level and wanted to walk through an option other than "just learn the notes."

JB: We don't "just learn" the notes any more than we might "just learn the pattern" of an Oriental rug. If someone does say something like "just learn the notes," it's intended as a shorthand for all the various *ways* we have to learn the notes: by muscle memory, ear memory (coupled with an assumption that what the ear can hear or remember, the hand can play!), noticing patterns, etc. Like so many things in this field, there are many ways to do it and we probably use multiple ways at once or at least at various times; and it's opportunistic. At least that's what *ought* to be meant by "just learn the notes."

STU 2: ...I remember you telling [another student] that he needed to learn efficient ways to learn a piece, and what I did last week with #3 was anything but efficient. I like patterns, as it makes sense out of the chaos. Visually, I prefer geometric patterns, even though Mom tried very hard to dress me in florals - and I wonder how this visual preference will play out aurally. (As opposed to Aura Lee.)

JB: Again, we have the nice situation where Everything is Good. Learning one way, good; learning a different way, also good. Any way you can think of to learn is good. Sometimes we think of a way that will work but seems as though it will be incredibly time-consuming; but if we go ahead with it, after a certain point we suddenly get much faster at it, or possibly we start seeing and hearing a bigger picture.

STU 2: Techniques: Try to fill input buffers in advance by looking ahead, without getting the contents of the output buffer mixed up in the process. My buffers find it easy to forget whether they are input or output when first learning a piece. The cat sits on my music books the minute I put them on the floor, so maybe I can recruit his paw for the "covering" phrase of the last bars on a line.

JB: If you succeed, you can start a sideline renting him out to other students.

STU 2: [Work on] phrase-wise memorization.

JB: Right.

STU 2: Look for discernable patterns; scale-wise progressions, or leaps that are notes of chords

JB: Right. Or anything else.

STU 2: Sing one voice while playing the other

JB: Important to have a "quiet mind" when doing this: very undisturbed, very focused. If you saturate after a certain point, don't push it but just go on to something else. Do keep track of how long at one time you can do it, though; how many bars, that is.

STU 2: Write in the actual notes of the upcoming bar at the end of the foregoing bar to help prevent "gaps"

JB: Yes; for the jumps from line-ends to beginnings of next lines.

STU 2: Memorize (which is the first time we've used that phrase in an assignment) the Melody piece. Get beyond "kinda sorta" and aim for "nailed."

JB: I bet it's as good as memorized already.

STU 2: Continue working on Russian pieces. I should have the book done by next lesson.

JB: Great!

STU 2: Continue working on Bart�k, focusing on the 1st and 3rd pieces especially - using the aforementioned techniques, realizing this might slow somewhat retard my "Excelsior."

JB: I look forward to hearing them (#s 37 and 39 I believe.)

STU 2: Continue on in Harmony I presume...I've just read about the dominant chords but didn't focus too much on that this week.

JB: Yes, please continue.

STU 2: Continue singing - and I am getting much more comfortable with M3rds, P4ths and P5ths.

JB: GOOD!

STU 2: By the way, I came close to forgetting to be nervous several times while playing for you – it must be the effect of Bee's new flea collar. If I were reading tea leaves, I would see this as a good omen – as well as being much easier on my neck. Since there is nothing even remotely ogreish about your teaching style, my taking 6 months to warm up might be a tad excessive, but better late than never, to quote Mr. Clich�.

JB: I'm very glad to hear it makes releasing your neck easier.

STU 2: Just spent about 15 minutes reviewing the first Bart�k piece and have it nailed now – using the "what is this phrase doing" method. Just about have the other one singable and can already see what that will fix. Cool stuff, Mister James!!!!

JB: Very glad to hear it.

I said, "You're playing the whole program tomorrow, so you shouldn't play it today. Instead, let's talk about keeping things fresh. What piece do you feel is getting stale?"

"The Beethoven sonata," she replied. (G Major, Opus 31/1.)

"OK," said I. "Do you like the mountains?"

"Yes."

"You like the air?"

"Yes."

"Imagine we're in the mountains, outdoors. We happen to have a piano with us. Do you remember what the wind sounds like in the mountains?"

"Yes."

"It can make different sounds, eh? Sometimes soft, sometimes loud." She nodded. "The wind has a repertoire, too. And the mountains have a repertoire. A repertoire of appearances, right? And even of sounds; an avalanche, for instance." Another nod.

"Please play the sonata now. Forget about human feelings; forget about musical structure. [Things we've spent lots of time on.] I want you to play the sonata for the mountains. You understand? For the mountains to hear." She nodded, her eyes large.

"OK, I'm going to sit down in the listening chair. Please breathe in mountain air, then play the whole sonata."

She sat contemplatively for perhaps 20 or 30 seconds, then played the sonata more beautifully than ever before. Her ear was more attentive, her hand more delicate. Everything was new, nothing stale.

Afterwards, I asked if she had any questions. She pointed out the imitative passage in the middle of the third movement and said, "I could not think of mountains on this page. Technique?" She meant, was this a problem in piano technique.

"No!" I told her; then asked, "Have you ever seen three mountains in a row; and a wind comes up which moves the trees on one mountain; then the wind reaches the next mountain; and then the third?" She nodded. I continued, "Or have you seen a large cloud throw its shadow on one mountain, and then on the next mountain, and the next?" Again a nod. I didn't have to say another word. She understood that the mountains I spoke of were the successive entries of voices in the imitation.

I gestured to the page and she played the passage beautifully and smiled when she finished. "OK?" I asked.

"OK."

On her score, by the opening notes of the sonata, I wrote, "Inhale mountain air."

Then I said, "Our lesson is over." She was startled, because it was so short. I explained, "I want you to remember this lesson. If we work on other pieces, you might not remember. This way, you will always remember the short lesson and what

you learned in it."

...Longy School of Music...

Notes on another unusual lesson with same student

(When image and metaphor work, they're fast. And they have a moral virtue: They leave the details of feeling and shaping to the student. And in this case, I could not feel that my image of grieving was out of line, given Beethoven's identification of the passage as a "sorrowing song.")

The �gesang� ends with four tripled 8ves in a simple cadential pattern. The rather "formal" nature of these notes, I suggested, could represent "the camera drawing up and back, moving through the roof of the house so that we see the village and the surrounding trees." (A rather formal ending of a scene, in other words.) When she played it again, it was alive and meaningful.

By the way, the 'she' of my sorrowing image is no one real; no one we�ve discussed; nor have we used film metaphors before. One of many wonderful things about this student is that she takes everything in stride. (Others are that she's gifted and intelligent, hard-working and serious; and that with her, �serious� does not mean �solemn.�)

Next we discussed a general approach to improving long lines in slow passages: practice them faster. (Everybody talks about "slow practice," which is counterproductive. No one talks about fast practice, which is useful.) Playing

faster makes it easier to hear the large-scale structure. In this case, you need to leave out many of the left-hand chords; but that's easy to do. She did it a couple of times, then played the passage at normal tempo; and both the line and the details of shaping were much better. She played more confidently, too.

Now we went to the opening of the Sonata, and found that she was so caught up in the "introductory" nature of the first four bars that she was actually playing them slower than what follows. This is unheard of for her, and maybe was due to the jet lag; but if not, I thought perhaps she was feeling impressed or intimidated by doing late Beethoven. I wrote the word "Significant" in large, fancy printing on the yellow pad she brings to lessons; showed it to her; then vigorously X'd out the word, at which she laughed.

One thing we're doing in the long-term is to pay attention to shaping and "chiaroscuro," the play of light and dark. As we continued working on the first movement, I suggested that a simple way of shaping is to think about moving up in pitch as working against musical "gravity.� I warned her, though, not to confuse this with a change in her body's level of physical tension! (That danger is the reason I had not suggested this before; but I feel confident now that she will not fall into that trap.)

Still in the first movement, we came to the broken chords that ripple down and up the keyboard. The ascending ones were fine, but on the descending ones her hand was making a sharp crab-wise movement at each downward jump of an octave. (Imagine looking at a top view of someone reaching left or right without moving the forearm.) The passage can be played with no angling of the hand. I asked her to practice this by playing the pattern twice in the same octave, so there was no jump, hence no angling; and then again with jumps handled by quick shifts of the whole arm.

Next we noticed that the right arm�s movement to the left was limited by the elbow and forearm fouling on the torso. When she leaned to the left earlier and farther, the problem went away and whole passage became comfortable � and more delicate in the playing.

We jumped to the B section of the first movement, and discussed Beethoven's staccato markings on certain notes. These seem to require that one not use pedal, which in turn makes the left-hand chords sound unconvincing. We didn't

come to any conclusion, but merely explored the alternatives.

Speaking of pedal, the end of the "Klagender gesang" has a pedal instruction that's hard to interpret. There's a 16th note followed by a 16th rest and then a repetition of the note. Damper pedal makes the rest vanish, of course; and Beethoven doesn't mark where the pedal is to come up. A footnote says that this text comes from the first edition; and that in the autograph � Beethoven�s manuscript � the 16th is an 8th. With that reading, using the pedal raises no problems because the note �sounds through� anyway.

There was much more.

VIDEO & AUDIO OF JAMES BOYK TEACHING AND PERFORMING, AND OF STUDENTS PERFORMING.

Know Thy Piano

A Musician's ABC

with young professional pianist from another country.

First lesson

With pianist Cynthia Sture and tenor Brent Reno.

(Indicating how musical and emotional issues, and some textual questions, are mixed with technical pianistic considerations.)

Speaking about "piano sound on both sides of the microphone."

For pianists, short essays on misunderstood basics. Includes Look Ma, No Pedal. Home in the Range. Stick Shtick. But Soft! What Sound Breaks Yon Window.

For musicians of all instruments, a essay for each letter of the alphabet. Includes A is for Aphorism. C is for crooked competitions. E is for efficient practice. F is for fear. H is for how music means. O is for over-complicated.

Inquire about lessons.

When you click on "Inquire about lessons," an email to me will pop up with questions that help me understand where you're coming from and where you want to go. Some students find the questions helpful in focusing their thinking. So go ahead and click, whether or not you end up sending the email. –JB

Copyright © 1997-2010 James Boyk.

All rights reserved to this and all other pages in this site.

Performance Recordings®

Performance Recordings Home | Books & Articles by James Boyk | Concert Albums | "Musician's Ear" microphone | Contact us